Down but not out

William Glass died of cancer in 1853 at the age of 66 and his death was the catalyst for an exodus of 25 family members to join relatives in New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1856. A further 45 people left with Rev Taylor in 1857, many settling in Riversdale, South Cape Province. As they left there were only four families, totaling 28 people in the world's most isolated community. Peter Green took over from William Glass as the unofficial spokesman (but never regarded as leader) of the community.

|

Maritime Motorway ClosedTristan da Cunha became increasingly isolated from shipping as a result of three important world events. The 1861-5 Civil War virtually curtailed the already declining whaling industry, whose ships had often called on Tristan for supplies. The Suez Canal's opening in 1869 gave a safer and much quicker passage to Far East markets, avoiding the perils of the South Atlantic and Cape of Good Hope. Finally steam replaced sail, effectively isolating Tristan da Cunha, which soon lived up to its modern Guinness Book of Records title as the world's most isolated community. |

Arrivals

Thomas Glass returned the surname to Tristan when he returned in 1866. HRH Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and second son of Queen Victoria, visited aboard HMS Galatea in 1867, after which the Settlement was officially (but never locally!) known as Edinburgh of the Seven Seas. 1878 saw the wreck of the Mabel Clark en route with coal from Liverpool to Hong Kong. Timbers from the boat are still visible in a Hagan family home, and a bell is in use in St Mary's Church. When Rev Dodgson arrived in 1881 on the ship Edward Vittery which was wrecked off the Settlement (possibly deliberately to claim insurance), Tristan's population had grown to 110. The insurance racket was repeated with more disastrous consequences in 1882 when the Yankee ship Henry B Paul was deliberately beached at Sandy Point (see Sandy Point Page). Black rats came ashore & caused havoc with seabirds and islanders' crops. Insurance companies became reluctant to insure boats sailing in South Atlantic waters which declined trade still further.

|

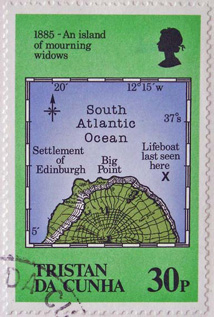

Lifeboat TragedyFew tragedies can have had such a devastating effect on any world community than the 1885 Tristan Lifeboat Disaster. With the loss of regular shipping and trading opportunities, virtually all of Tristan's able bodied men (15) decided to attempt to trade with the ship West Riding when it sailed off the island on 28 November, despite unfavourable weather. Sailing in a newly donated ship's lifeboat, they rowed out of sight eastwards, beyond Big Point and were never seen again. The incident remains a mystery, but the 15 men were missing, presumed drowned as their lifeboat probably capsized in rough seas. When the ship City of Sparta called on 26 December the population was 92 - with 13 widows left by the tragedy, and only four adult men including Peter Green (77) and Andrew Hagan(69). |

||

Departures and Arrivals

Rev Dodgson returned and the British Government set up an annual supply ship to help the beleaguered community. The islanders were offered a free passage to Cape Town, but only 10 people left with him in 1889. A further 13 emigrated in 1892, leaving a population of only 50 It was again shipwrecks which came to the aid of the lonely island. The Allenshaw was wrecked in 1892, and the crew, led by Captain Cartwright, helped the community, particularly by assisting the women to tend the Potato Patches. In the same year the barque Italia caught fire in mid-ocean and successfully beached in Seal Bay. Two of its crew, Andrea Repetto and Gaetano Lavarello of Camogli in Italy, stayed behind and added their Italian blood and surnames to what was becoming again a viable community which consisted of 74 people in 18 families by 1899.

Self-Sufficiency

The island community re-grouped and honed skills of self-sufficiency, relying on hunting and gathering trips to Inaccessible Island using new longboats thought to be developed by the carpentry skills of Gaetano Lavarello. Eggs and meat from albatross, shearwaters and penguins, supplemented sometimes scarce farm produce. In 1906 almost 400 head of cattle were lost due to over-grazing of depleted pastures in unusually dry weather, which also meant a very poor potato crop. But no-one starved, and the islanders had the benefit of Rev and Mrs Barrow's ministry and teaching, landing at a north-east beach still known as 'Down-Where-The-Minister-Landed-His-Things' including a harmonium. In 1908 two Glass brothers returned married the Irish sisters Elizabeth and Agnes Smith who proved influential in teaching and founding the Roman Catholic faith on the island - see Churches Page

Isolation and ProgressTristan’s most isolated period was during the First Word War when the Admiralty abandoned the annual supply ship voyage (as in the Boer War) and it is reported that Tristan had no incoming mail for ten years until HMS Yarmouth brought news of the armistice in July 1919. The 1920s saw the ministry of Rev Martin Rogers who organised the building of St Mary’s Church and ran an expanded school in Andrew Hagan’s house (see Churches and School pages). The first scientific expedition to Tristan da Cunha was carried out by a Norwegian team led by Dr Erling Christopherson, and including Allan Crawford as surveyor, who completed the first detailed land-based map of the island (see President’s Page). |

|

||